Imagine this. A film has just hit theatres. Reviewers are competing with each other to put out their opinions. People are taking pictures while watching the film to provide evidences of their understanding on social media. They are dissecting every frame, and every composition, and express their wonderment about those frames and compositions. Contrary to before, the respect for the cinematography is not tucked into some neat corner of a review. It is now out there for everyone to consume and celebrate.

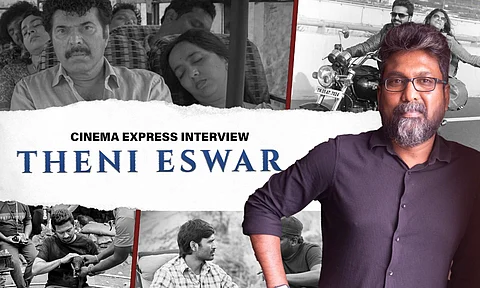

Cinematographer Theni Eswar, whose frames in 2023 through Nanpakal Nerathu Mayakkam (NNM), and the recently released Maamannan, feels this healthy trend gives the viewers a chance to appreciate the technical aspect while enjoying the story. Frames have become an integral part of Eswar's life, and he seems to even subconsciously look at life in the form of compositions. Asked if his craft has the power to change the way we look at people, Eswar's eyes gleam with an energetic yes as he gives an example of the renaissance of Vadivelu. “We went for a complete no-makeup look. To subvert the gaze of humour, we played with lighting, camera movement, and lensing. Just like seeing a sun in the morning and noon is different, the way of lighting and choosing lens also elevate the dimensions of these characters.”

Trusted with the responsibility of turning powerful scripts into equally if not more powerful visuals, Eswar majorly relies on his technical prowess with lighting. “In Maamannan, we have Adhiveeran, Maamannan, and Rathnavelu who is more powerful than the first two. For Rathnavelu, we diffused the lights and made them gloomy and soft. Whereas for the protagonists, we recreated natural light through sources like windows. We cut the light and maintained a shadow for naturality. The way of lensing, lighting, and composure is the key.”

While as much as Eswar plans for the shoot during the recce, the technician is up and ready when working in dynamic scenarios. Collaborating with someone like Mari Selvaraj for Maamannan, Karnan, and Vaazhai (upcoming), who is known for improvising on the sets, provides Eswar with an interesting challenge. “Working with (Mari) Selvam means anything can change anytime, from dialogues to sequences. I am prepared to shoot it raw. For instance, in the flashback portions of Maamannan, I had to show the majestic cliff, suggesting royalty as well as the loneliness of Maamannan. As he cries by the cliff, he is isolated amid the big mountains. We shot in shallow depth of field, black and white, with Vadivelu sir in focus,” explains Eswar, throwing light on one of the most appreciated sequences of Maamannan.

Apart from his still photography background coming in handy, Eswar’s prolonged discussions with the filmmakers are key too. This particularly helps when Eswar has to work on films like Karnan and NNM where the interpretations of imagery are aplenty and frames go beyond just spoon-feeding the audience. In NNM, for instance, frames were hailed as paintings, and gave rise to multiple fan theories. “For NNM, we wanted a corn field that was ripe for harvesting, to shoot the sequence where Mammootty sir gets into the village for the first time. We thought the harvest can mean different aspects. We scouted for the location for 15 days and couldn’t get it for a long time. What we got was something similar. It is not that he just gets off the bus. Every shot can be made poetic, which can make the audience believe in the world of storytelling. For that shot, we had created the road, and street posters, and only if we set up at least half a kilometre, we can keep a wide shot. So, a director’s support for our vision of their imagery is important,” Eswar explains.

So, does that mean each dot per inch of his frame is planned? A fan of details, Eswar nods a confident yes. He says, “The moment Mammootty sir becomes Sundaram, our shots become static. It is about a drama troupe and the film itself raises many questions about life and philosophy in multiple layers. We wanted multiple interpretations to linger on the viewers and opted for staged static shots. They give you space to connect with what the film is trying to say. We staged every detail, right from the posture of the animals to where the artists should stand.”

Known for his work in films like Merku Thodarchi Malai, Aelay, and Karnan, another striking aspect of his cinematography is Eswar's understanding of the terrain. “The lights I create cannot be separated from the natural source. The more we take natural light, the more it enhances. For example, Peranbu was shot during winter. It is important because each weather varies in the tone of colours, temperature, and light approach. It’s a film that is full of life and colours. When we shot in December in Kodaikanal, the soft light made colours pop up. In Maamannan, it was peak summer and colour changes supported the script. In the post-interval sequence where Vadivelu and Udhay sir sit, we sourced light to make it natural. In Karnan, the sun plays an important role since the hero is hailed as the son of the sun. We tried to incorporate that into the frames through silhouettes.”

All said and done, Eswar is a firm believer that the film’s soul is carried within the script and that his camera is a mere tool working to elevate it. “I have worked with strong voices, and it is through them I believe that cinematography has become an art to savour. A scene might be written for pages together, but visually it can be covered in one shot. But behind that one shot, are plenty of conversations,” Eswar signs off.