It was the year 2008, and I was a freshly-minted postgraduate working for a city newspaper as a journalist, covering the arts and culture beat. It was also the year Nandita Das made her directorial debut with her incredibly subtle Firaaq (in the aftermath of the 2002 Gujarat riots). It was a film about violence, the worst of human qualities, and hatred, that didn’t have a frame of violence in it. I clearly remember speaking to Nandita, even today ten years later. Because she spoke eloquently about the need for the female gaze in our cinema, and that conversation would sow the seeds for my interest in the gender discourse around cinema and eventually lead to this column. The essence of our interview from ten years ago was that undermining of women is one thing - and the way it finds itself on screen another - but because of the former, the way the general (male) gaze represents women is so often so skewed.

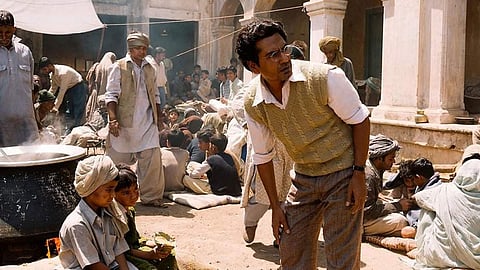

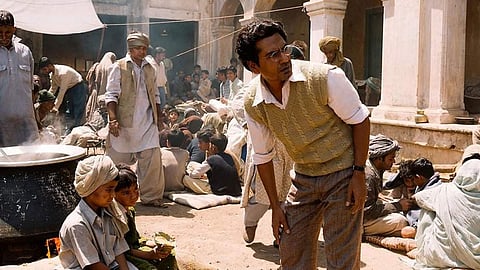

A decade later, Nandita is back and at the heart of her film is a real man, a storyteller, the author Manto (a crackling, different Nawazuddin Siddiqui), who’s told on screen, “Your stories always show a special empathy for women.” To which he says, “Not for all women. Some for the one who isn’t selling herself, but is still being bought. And some for the one who works all night and sleeps in the day, dreaming of old age knocking at her door.” Nandita showcases the poignancy of the female gaze – by balancing the frames between the man, his prowess and his fears without diminishing others around him. In the hands of a lesser artist, Manto might have been made into a larger-than-life, extreme character, what with this great art that will go on to outlive him, his pain over the Hindu-Muslim divide and the India-Pakistan divide, his descent into alcoholism and his paranoia and of course all the rich material that is his own writing. But Nandita handles it all lightly, without being burdened by the man’s genius. She shows him in the best light possible – a flawed, real flesh-and-blood human. An artist who cared about others’ opinion, particularly those he held high. As a writer of short fiction, I understood Manto’s insecurities too, I felt it through Nandita’s steady gaze. Be it the women who were the centre of some of Manto’s stories that has been woven into this script, or the women around Manto (especially his wife Safia – the charismatic Rasika Dugal), no one stands small just to make Manto tower. They are all equals in this equal journey. That is the nuance, the female gaze brings to cinema.

Nandita’s two-film-old, decade-long directorial career has an interesting continuum – exploring the fractures in the fabric of our society – investigating just where this Hindu-Muslim divide that has gripped us comes from and where it is taking us, this time in the aftermath of partition.