In a scene from Manikandan's Kadaisi Vivasayi (2021), Ramaiah (Vijay Sethupathi) talks to the protagonist Mayandi about a conversation he had with Lord Murugan. Ramaiah refers to Lord Murugan as his friend. Unlike the rest of the village, Mayandi doesn't alienate Ramaiah, and actually indulges him. For them, divine visitations are neither odd nor irrational. Yes, he is supreme. Yes, he is a heavenly being. But for them, he is one of them.

The Tamil epic Thiruvilaiyadal Puranam and the timeless classic of director AP Nagarajan's Thiruvilaiyadal continue to inspire the idea that God can dwell among humans. It talks about how a fervent call from a devotee can bring them from their heavenly abode. Take the case of Palayathu Amman where the titular goddess doesn't think twice before eating rice gruel or sleeping on the floor of her devotee's abode. Oh, in our films, we have even seen Gods sort out the love life of his devotee (Seedan), and give them a sense of reality (Arai En 305-il Kadavul).

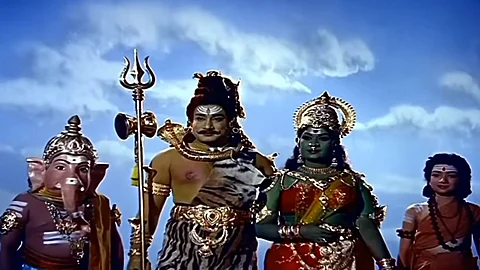

While the epic has over 60 episodes, director AP Nagarajan picked a handful to showcase in his film. If the Dharumi (Nagesh) and the Hemanatha Bhagavathar (TS Balaiah) episodes added commercial value to the film with humour and music, there are takeaways from the other three episodes too.

As the evergreen Sivaji Ganesan-Savitri starrer turns 60, here's a deep dive into the film's themes, and how, while instilling spirituality, the film tells us that some healthy amount of iconoclasm from time to time is required to replenish the religion. With each of these segments, the film condemns ego and excessive pride, even as it propagates humility and promises rewards for unflinching faith.

Right to Dissent

The word religion, in several cultures, is an institution that commands unquestioned respect and obedience. Thiruvilaiyadal begins with an act of dissent. Parvati (Savitri) attempts to pacify her irate son Murugan (Susarita) and dissuade him from moving away from his family for being partial against him in awarding the gnanapazham to his brother Vinayagan. He was not threatened with ostracisation for raising questions. On the contrary, the epic has it that it was after this fallout that Murugan began his reign over Pazhani and He was and is still exalted as the Tamil Kadavul, even across shores. The story stands to testify that no one is above question or scrutiny, even God. If there is merit to the questions raised, God is kind and merciful enough, to even reward the act. Similarly, Nakeerar (AP Nagarajan) finds fault with the poem composed by God himself. The message these stories impart are relevant to the times we are living in, where even questioning a dispensable government is viewed as a cardinal sin that deserves reprimand.

Humility over Knowledge

The biggest Achilles heel of the Hindu faith is the birth-based social strata. The apologists argue that the system was formed based on work and then was corrupted into a birth-based hierarchical system by humans. There could be some truth to it. But that is in no way a justification to deny what it is or what it has morphed into and the inexplicable evils it has wrought in Indian society. There aren't obvious references made in the film about caste discrimination. The point, however, is conveyed right from the entry of the haughty Hemanatha Bhagavathar (TS Balaiah). With his entitlement, he vows to enslave the whole of Pandiyanaadu (present-day Madurai and nearby districts). On the contrary, the cowering yet devout Paanapathirar (TR Mahalingam), whose lack of sangeeta gnanam could put Pandiyanaadu on the line, seeks divine intervention. Lord Shiva (an effortless Sivaji Ganesan) appears as a Paanar (a musical community considered as an outcast), the community to which Paanapathirar belongs. Unlike in other Bhakthi films where God endows his devotees with extraordinary powers, here God humbles himself as Paanapathirar's student, with the intention that the arrogant Bhagavathar should run away ashamed without a contest to His 'mentor.' Making Paanapathirar a Carnatic exponent in the blink of an eye would have been easy for God. But then it would have been a battle of 'who has mastered the art form,' with no commentary on the individuals' personalities. Paanapathiran should trump the Bhagavathar while remaining Carnatic illiterate. 'Arivaai Manidha Un Aanavam Peridha?'

Vernacular Veneration

There is an interesting tradition in Vishnu temples of Tamil Nadu. It has the reciters of the Sanskrit Vedas following the Lord's chariot, and the chariot follows those who recite the Tamil Hymns of Azhwars. This tradition signifies that when Sanskrit is still in search of God, God is besotted with Tamil and follows it. It would not be an understatement to say that worshipping in Tamil has somehow opened the floodgates for other communities to sing praises of God in their mother tongue: the Abhang tradition in Maharashtra, the Baul tradition in West Bengal and Bangladesh, and scriptures getting written in the layman's Awadhi. Thiruvilaiyadal, similarly, is not just a eulogy of the Lord, who chooses to live among mortals to impart life lessons and share people's hardships. The film also tells of the Almighty descending to earth for His selfish reason to be in the company of Tamil scholars. When Shiva is done alleviating Tharumi's (a snarky Nagesh) poverty and showing Nakkeerar his place, he tells Nakkeerar, "Un Tamilodu Satru Vilaiyaadave Yaam Vandhom." Likewise, a riled-up Murugan, who stops for none when leaving his parents, didn't budge when the celebrated Tamil saint-poetess Avvaiyar began her recital. With all due respect to the language, the liturgical emphasis of Sanskrit makes the concept of God esoteric, making Him seem unattainable for a commoner. Tamil, however, with its irreverence (not disrespect), has brought God closer, like one of our family members.

Without Shakthi, there is no Shiva

This may not look radically revolutionary for today, but back in the 60s, when a woman was expected to be clingy and say, "Naatha, Swaami, Aththaan," no matter how bad a husband was. Even Parvathi does this for some time before challenging her consort into a battle for visiting Her father without His consent. The battle ends with Shiva bringing Parvati back to life and conceding that He is incomplete without Her and transfiguring in a way that She is half of Him. This can be seen as a freedom to express dissatisfaction, even towards God, particularly for women in their relationships with husbands, especially in a time when marriage was viewed more as servitude than as a partnership. As KP Sundarambal's Avvaiyar sings, "Thaan Paathi Umai Paathi Kondanavan Sari Paathi Penmaikku Thanthaanavan."

Social Relevance

Devotional and mythological films are often disconnected from reality and modern issues. Thiruvilaiyadal, surprisingly, has ticked this box as well. Again, not in an obvious manner. Server Sundaram, which was released a year before Thiruvilaiyadal, will have an elaborate theatre play where Nagesh's Sundaram will reach heaven to voice his complaints about his life and God will respond, saying that He cannot be made responsible for every wrong decision a human makes and urging him to follow government policies such as family planning. Though set centuries ago, before the 20th century, Thiruvilaiyadal would have made way for addressing present issues. Take the song 'Paarthal Pasumaram,' God sings, 'Ponnum Porulum Mootta Katti Pottu Vechchaaru, Ivaru Pona Varusham Mazhaiya Nambi Vedha Vedhachchaaru,' which seems to highlight the drought situation in India during the 60s and emphasising the family planning policy and showing concern towards women who are forced to bear numerous children due to societal pressure turning a blind eye to their health, in the line, 'Paththupulla Peththa Pinnum Ettu Maasama Indha Paavi Magalukkentha Naalum Karba Veshama.' In the 1960s, attacks on fishermen began, straining relations between India and Sri Lanka. In the episode where Parvati takes birth as a fisherwoman, she wails on a couple of occasions that God is partial in his creation by endangering the fisherfolk while placing the rest of the population in relative safety. Be it 1965 or 2025, we know for a fact that the shark that threatens the fishermen in the film also works as a metaphor.

This piece doesn't emphatically declare that AP Nagarajan has made the film the way I looked at it. Tamil cinema, in general, was split into two eras. One is the bhakti film era, decried as the public apathy era, and the subsequent era is the social awareness era, where films increasingly discussing contemporary issues were made. I found the convergence of both eras in Thiruvilaiyadal. APN best knows why he handpicked these five incidents from the Thiruvilaiyadal Puranam. I am sure he wouldn't have gone with the five without rhyme or reason. Is this my way of looking at this classic or was it made to be perceived this way? I cannot know. But whatever it is, Ellam Eesanin Thiruvilaiyadal.