Where daughters break and mothers bloom

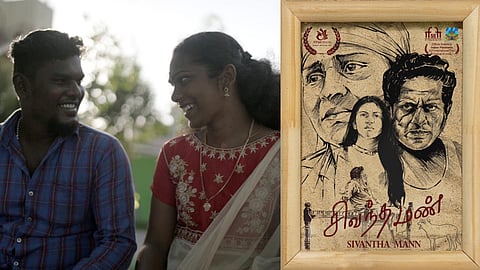

It’s fascinating how patterns emerge between films screened as part of a double-bill, as though stories whisper to each other across genres and formats. On Tuesday, the sixth day of the 55th International Film Festival of India, two Tamil films—Sivantha Mann (directed by Infant) and Amma’s Pride (directed by Shiva Krish)—brought to life the struggles of protagonists who are othered, boxed out by a society that denies them even the most fundamental joys. In Sivantha Mann, it’s a woman stripped of the dignity of her labor, denied the right to her wages. In Amma’s Pride, a hybrid documentary, it’s a transwoman fighting against the dual walls of law and prejudice to marry the man she loves. Beneath these struggles, layered across both narratives, there’s a common theme: these are films about mothers—beautiful, unwavering mothers.

In Amma’s Pride, which blends interviews with dramatised moments, the mother of Srija, the transwoman protagonist, stands as a radiant beacon of love. She isn’t an activist fighting inner prejudice, nor a character grappling with societal expectations. She’s simply a mother, her heart beating instinctively for her child. Isn’t that, after all, the truest antidote to systemic hate—the simple, unshakeable love of a parent? When society rears its ugliness, when prejudice seeps into homes and poisons relationships, a mother like Srija’s shows us the possibility of purity. Were a transphobe to question her love for her daughter, her response wouldn’t include words like “tolerance” or “understanding.” She wouldn’t even comprehend the premise of the question. Her love, unencumbered by judgment, is as instinctive as a sunrise.

Sometimes, we believe love must emerge from a place of great thought, of painstaking introspection. We think it requires wisdom to rise above prejudice, but Amma’s Pride quietly undoes this notion. Srija’s mother, in her awkward interviews, lays her soul bare with startling simplicity, showing us that the best love—the love that transcends all barriers—is instinctive.

In Sivantha Mann, the mother’s love is more outwardly cinematic. She is a figure of toil, scampering across fields to serve a sadistic landowner, her life a mosaic of labor and humiliation. She cleans his fields, endures his abuses, and even swallows the indignity of unpaid wages. The film doesn’t sanitise these cruelties; it lets them linger, forcing you to sit with the weight of caste and class dehumanisation. The landowner’s venom drips through sharp, cutting abuses, and yet, in the film’s fantastical happy ending, the tide turns. He is repaid in kind, humiliated, cussed at, and dethroned—if at least, for a few brief minutes.

And yet, what stayed with me was not the poetic justice, but the quiet rebellion that followed it. Amid the barrage of curses, the woman’s daughter walks up to the once-feared landowner and delivers a single insult: “Nee dhaan da loosu.” I laughed out loud, the simplicity of her words cutting through the elaborate theatrics.

These films aren’t flawless. They aren’t polished to perfection, nor do they strive for structural brilliance. And that’s all right, for they brim with sensitivity, with an unyielding compassion for those who are pushed to society’s edges. For all their darkness—the horrible people who populate their frames—they gift us with moments of light: a mother’s unshakable love, a child’s rebellion, the breaking points that lead to uprising.

After all, as Kamal Haasan says in Kuruthipunal, everyone has a breaking point. In Sivantha Mann, that moment births an uprising—a flicker of hope amid despair. In Amma’s Pride, Srija meets hers over and over again, but her mother is always there, steady as an anchor. These films, in their own ways, remind us that even when all else feels lost, sometimes one person’s love is enough to keep us going.