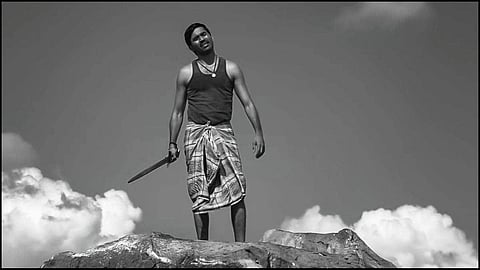

Black and white paintings adorn the walls of Mari Selvaraj’s bustling office. Welcoming you into his office is a large painting of Arya Stark on horseback, wearing her sword. There are other paintings: of warriors, of gladiators brandishing their swords; paintings that radiate the burning spirit of his new film. Two of them, especially, belong intimately and spiritually to the world of his Karnan. One is of a Herculean king, on an elephant, wielding a sword and riding alone in the wilderness. Remember the majesty of Karnan on an elephant after triumphantly slashing a fish into two in the village ritual. His legend as the chosen one is cemented here. The king in the painting, however, seems uncertain, a look of alarm visible on his face, as he considers the potential dangers lurking in the woods. Another imposing painting is placed above the filmmaker’s upholstered chair, in the intimate confines of his room. It is a recreation of an iconic frame from Game of Thrones: a shot in the Battle of the Bastard episode, that has Jon Snow wielding a sword, ready to take on the swarming soldiers of Bolton. Snow, like Karnan, suffers condemnation for the illegitimacy of his birth, and is always reminded that he does not belong. He owns and ‘knows nothing’, and yet, rises to fight for his land. The story and emotional relevance of these paintings is quite clear.

Karnan, the director’s sophomore outing, is a saga that is subversive, searing, and thrillingly surrealistic. The narrative assumes the staggering proportions of an epic, leaving you suffering an overwhelmed silence. Interestingly, the director’s first book, ‘Thamirabaraniyil Kollapadaathavargal’ had a short based on the Thamirabarani massacre of July 23, 1999. Impelled by the horrific event, Mari’s short is about revolution, police brutality, communal violence... In Karnan, a world haunted by the murdered, the survivors, like in the short, rise in revolt in a story partly based on the Kodiyankulam riots of 1995. Mari Selvaraj has created and positioned his world with an auteur’s finesse, with a dreamer’s passion.

Here is an exploration into his ambitious second film that establishes him as an irresistible force in Indian cinema:

The Mahabharata parallels

Mari’s debut feature, Pariyerum Perumal, followed the journey and struggles of Pariyan, who is confronted with the hostilities of the world in a law college. In Karnan, even before a young girl can get to a college, violence erupts and cuts her wings. The struggle begins earlier here and is more primal and vehement; violence becomes inevitable. The happenings are also set further in the past, nearly eight years before the events of Pariyerum Perumal.

There is strong subversion at the film’s core, a subversion of artistic and socio-cultural relevance. The film’s eponymous character is inspired from the Mahabharata and the narrative is a critical reading of the ancient saga. Karnan in the epic is a tragic hero, raised by a family of charioteers who are of a lower social status. The film removes the idea that Karnan is blessed with divine boons; in the film, he suffers losses and has to make himself heard. Mahabharata is a sprawling twisted tale with myriad complex characters, in which moral boundaries often get blurred. A main preoccupation of the Bharata is the fight between the just and the unjust. Karnan too is a quest for justice and equality, one that rages with fury.

The Mahabharata parallels are very many. Karnan characters are bestowed with royal names; the film even has a gambling scene which sees conflict and tension. The villainous symbol of oppression and the brutal abuse of power is a policeman called Kannabiran. While in Mahabharata, it is Krishna who breaks the truth to Karnan about his birth, in this film, Kannabiran is shown harbouring deep prejudices towards Karnan on account of his identity. He expects subservience. Mari also sparks an intimate romance between Karnan and Draupadi, a romance forbidden in the original saga due to communal differences; many retellings of the tale speak of how the Queen pined for her unrealised love. Through his fascinating subversion, Mari Selvaraj reshapes the identity and destiny of his characters.

An earlier significant adaptation of Karna’s story in Tamil cinema was Mani Ratnam’s Thalapathi (1991), which was more invested in the emotional dynamics of a boy’s aching quest for his mother’s love. In the film, Surya (Rajinikanth) is constantly harassed for the illegitimacy of his birth and one of the major conflicts is his confrontation with authority figures including the police and the collector. The film, despite touching upon caste and identity, does not venture into a deeper exploration. Yet, it did speak of the tragic romance between Subbulakshmi and Surya, who ends up marrying the more educated, Surya’s half-brother, Arjun.

It has taken Tamil cinema three decades after Thalapathi to see another powerful, original adaptation of Karna’s story, which narrates a remarkable story of dissent. In Karnan, Dhanush aspires to be a soldier and later turns into a rebellious warrior figure. Echoes of the Surya-Deva dynamic can be found in the endearing relationship Karnan shares with his old granddad, Yeman. Karnan’s Draupadi also has more agency than Subbulakshmi. While Mani Ratnam’s interest was concentrated on the emotional core of his film which led to the negation of its own politics, Mari Selvaraj’s film benefits from the filmmaker’s focus on the interaction of his characters with the forces of their world.

The poetry of Mari Selvaraj

The filmmaker also actively and passionately draws from his own life, as he has repeatedly confessed. The origin and rootedness of Mari Selvaraj’s art in his own life lends an immensity and piercing quality to his art. Recall how post his banger-hit ‘Enjoy Enjaami’, singer-songwriter Arivu shared, “I don’t want to be a political artist. I want to be a real artist. But being real is being political right now.” These words explain why the realism of Mari Selvaraj’s art is politically charged. Actor Vallinayagam, one among the many talents introduced in Karnan by the filmmaker shared a brief personal note on Facebook after the release of the film’s folksy song, ‘Manjanathi Puranam’. He recounts joyously spending time on the shoot of this song that bears the name of his grandmother. When sharing this with the director, he was startled to learn that the latter’s grandmother too had had the same name. It’s an anecdote that reveals the intimate relationship Mari Selvaraj’s art shares with his life, and with those around him, as he chronicles the poetry, power, and struggles of everyday life of these people. He is not merely documenting reality though; he poetises and fictionalises reality to suit the needs of his cinematic art.

During the press meet of Karnan, the director addressed a deeply existential question encircling the minds of artists, “Who am I? What is the basis of my art?” Mari Selvaraj replied, “I am a poet. I build my film, my shots, with the precision and poetry of verses.” He shared how he raised Karnan like a fire, how he fuelled the flames crackling in the darkness of its nights. Karnan, the character, too is naturally all fire.

In his book, Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky wrote about the poetry of a filmmaker and its implication on the filmmaker’s art while discussing the art of Luis Bunuel. Tarkovsky wrote, “Bunuel is the bearer, above all else, of poetic consciousness. He knows that aesthetic structure has no need of manifestos, that the power of art does not lie there but in emotional persuasiveness.” It’s the sort of commentary that even in these early days of Mari Selvaraj’s filmography, seems to apply to him. His awareness of the aesthetic structure, his poetic consciousness, and his quasi-musical and eloquent visual treatment of his film has avoided the risk of his politically profound film being slighted as propaganda, or ‘another moralising mass movie with a message’.

The nature of poetry lends itself to profuse imagery and metaphors. Karnan, naturally, has striking metaphors in its world: the horse, donkey, sword, folk deities... All of them combine to achieve a powerful emotional and aesthetic impact. The poetry of the maker brims both in the polychromatic initial half of the film and its urgent final act. The major conflict is introduced only around the interval point. This is also true of his first film in which he leisurely weaves episodes from the chequered student life of Pariyan before he gets abused in the marriage hall and realises the prejudices around him. The interval point in Pariyerum Perumal is emotional depression, while in Karnan, there is a rousing uprising that screams liberation and poetic justice.

The poetic liberty the filmmaker revels in is evident even in the very first song where he subverts the hero introduction trope of Tamil cinema. He wreathes Karnan in glory, yes, but it’s a melancholic lament that summons a captured guardian. Amid the dark of the night, his memory alone blisters into flames and light. This is a visual play of light and darkness, of day and night in the opening ballad. It breaches the barrier of the screen and transcends into our reality. It makes us invested; we too ache, mourn and cry out for Karnan.

Cinematic resonance across the world

The political and artistic resonance of Karnan is universal. There are echoes to Kurasowa’s classic Seven Samurai, with both films centering around villages under attack. In Seven Samurai, the villagers seek their protectors outside. Here, an individual’s rebellion results in a unified uprising of the village. Karnan also shares a crucial spiritual connection with the blisteringly political 2019 Brazilian film, Bacurau directed by Kleber Mendonca Filho and Juliano Dornelles. The film, streaming on MUBI is the story of an isolated village in Brazil that is cut off from water supply, internet and is subsequently erased from the nation’s maps. Faced with Western invaders empowered by local authorities to destroy the village, the villagers rise and revolt, defending their land under siege. The eerie and pulpy Bacurau bears a significant metaphor of a bird which gives the film its title.

Karnan too bears the metaphor of a bird, a thieving eagle that preys on nestlings. It’s a recurrent reference in the film, in both visuals and dialogues. Every time danger runs close, Karnan is warned that he will be pecked and snatched away. In the village gathering, a devastated Duryodhanan prays that the youth of the village fly away somewhere, away from the crushing oppression. In the stirring war anthem, 'Utradheenga Yeppov', Dhee sings, “We are going to fly all around the world, where are our wings?”

In Bacurau, we don’t see the hunting bird that the village is named after; we only hear of this bird that symbolises power and liberation. It is said to come out only at night, almost like a vigilante. This genre-defying film was acclaimed for its subversive take on Westerns and horror thrillers. These tendencies of the film bind it to Karnan. This does not imply that the existence of one film inspired the other, but that the presence of such films independent of one another, drawn from the politics of their respective lands, stands testimony to the universality of art.

The anger rippling in Karnan also reminds you of the 2019 French film, Les Misérables: “What if voicing our anger was the only way to be heard?” The very fact that Karnan can be talked about in immediate relation to Bacurau and Ladj Ly’s Les Misérables echoes the sentiments and sensibilities of these artists, and the social tension seething in their respective lands. Les Misérables, alike Karnan, was inspired by a real riot, specifically the 2005 Paris riots that shook France. Les Misérables is set in 2018, Karnan in 1997 and Bacurau in the future. It is chilling to note how three films hailing from completely varied cultures, set in different times unite in their central social theme and contemplation, revealing the reality that there is a long way to go for many societies across the world. It is fascinating how these three films position children at the forefront of definitive narrative situations; it becomes a commentary on the horror of generational angst being passed on to them and the urgent need to free them all from the terror.

An ecosystem of art, and the love for symbolism and animals

With Karnan and its portrayal of life in Southern Tamil Nadu, Mari Selvaraj has also reinvented neo-nativity in Tamil cinema. He films his stories in his native village and creates his art with the passionate involvement of villagers hailing from the region. Even in the cases of Bacurau and Les Misérables, the filmmakers filmed their stories in actual locations of the story’s setting and largely involved locals to act prominent parts to make their film more rooted. Empowerment of local talent and embracing nativity prove to be universal features in the new age social cinema.

Besides striving for rootedness and nativity, Mari Selvaraj’s cinema also strives to create an aesthetic that evokes something raw and exotic. Remember the monochrome lyric video of Uttradheenga Yeppov. Singing in the dark amidst smoke filling the night, Dhee was cloaked in a black cape. With posters of the film and the fabled sword of Karnan left alone and unattended, the song had an enchanting Gothic vibe to it. Dhee looked at once like a vigilante and a guardian angel, a contemporary semblance of Kaatupechi.

The donkey is a potent metaphor in Karnan. It signifies oppression, an oppression that distorts the free nature of the being, resulting in its domestication and slavery. The bound legs of the animal eerily invoke images from Karnan’s posters, where we see him, wounded, his hands chained. There are scarce empathetic portrayals of the animal in cinema, given that they are usually degraded beasts of burden. How many filmmakers have ventured to inquire about the nature of this animal, how it is treated and what it says about society's psychology? A touching portrait of the animal I can recollect dates back to the 60’s in Robert Bresson’s French film, Au Hasard Balthazar. The donkey is the titular character called Balthazar. The French auteur deeply explores the Christ-like suffering of the animal, human cruelty, and the plundering of its innocence. Balthazar, the donkey, is a metaphorical representation of Prince Myschkin in Bresson’s highly idiosyncratic adaptation of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot.

Animals and nature form an important component in the world of Mari Selvaraj, be it Karuppi in Pariyerum Perumal, or the magnificent black horse and the donkey in Karnan. They are primarily tied to his films where life coexists with elements of nature, with the heat, the rains, pigs, and goats. They also seamlessly enhance the mood of the film, subtly invoking the external and internal world of the characters. When Karnan’s family pleads him to dig the floor during the dead of the night, the dog is stirred awake and a cat steps out of its shelter as he lands the first blow. As the earthen pot breaks, a horse neighs in the night. With secrets and treasures unearthed, a stronger mental torment also awakens in Karnan at that point, taking possession of him. It is an awakening of repressed sorrow and painful memories which come to haunt the present. The worms crawling over the coins is another visceral image which returns with an eerie edge in the scene where Kannabiran pierces them to the fishing rod. The imagery bears great symbolic weight. While the worms are held tenderly as protectors of treasure in one’s hands, they are mercilessly used by another as mere prey.

Death is just the beginning

Talking about Karnan, Mari Selvaraj hailed how he had mounted the film on Gods. Post the prelude song, the very first shot of the film shows a sun rising in the backdrop of a beheaded idol. These are gods, subaltern deities who rise to divine stature by their stories… stories of injustice, of valor, tragedies, and rebellion. Karnan starts with the death of his sister. The camera pulls away as she breathes her last on a cruelly indifferent road, and when it descends on her again, she has moved from life to legend. The filmmaker’s stories always begin with death, be it his two films or two books. Karuppi’s death and the funeral cries opened Pariyerum Perumal. Death, in some crucial way, prepares all of us for life, initiating us into it, pushing us to probe it. If the death of Karuppi was the initiation for Pariyan, making him aware of the ruthlessness of communal hatred, the death of his sister creates a similar jolt in Karnan. It is his initiation into the realities of his world where some lives don’t matter.

As he utters later in the film, the death of his younger sister is why he is what he is, why he burns with a fire for rebellion and liberation. Karuppi rises with an exhilarating metaphorical bearing in Naan Yaar, and Karnan’s sister rises, her spirit and suffering multiplied manifold in the war anthem of Karnan. Her haunting and powerful omnipresence in the narrative gives Karnan a unique folkloric surrealism. When the bus is wrecked in the interval point of the film, the freed donkey goes to the spirit of Karnan’s sister that wanders by the hills. Karnan unleashes all his angst and stands by the idol of the goddess whose spirit watches over him from the hills.

Karnan’s legend of being the chosen one begins with him winning the fabled sword. The sword evokes ‘Excalibur’ from the Arthurian legend. An intriguing point of connection is that some legends claim how Excalibur was gifted to the King by the Lady of the Lake, and when he was fatally injured, the king apparently ordered it to be thrown into the waters. There is a similar sequence in the film involving the sword when Karnan’s mother throws it in the pond believing it to have brought misfortune upon her son.

War and peace

There are several battles throughout Karnan which lead up to the climactic war: the fight in the cattle farm which exudes a Texan ‘wild west’ feel, the wrecking of the bus and police station, blows to the abuse of authority… With every battle being more menacing than the last, Podiyankulam finally goes to war. As a reactionary film and narrative, Karnan is impressively sensitive. Violence is not treated as stylised orgy. Even the violence and what necessitates it is utilised to probe something existential and tragic.

When the village rises and readies itself for war, heavens erupt into pouring rain before the long night and the fateful dawn. The thundering rains create a fine atmospheric chaos, signaling something decisive after the prolonged heat of oppression that has scorched the village dry. The rains and Karnan’s rebellious roar summon the verses of Mari Selvaraj himself, “உனக்கென்று அடுத்த முறை நான் வருவேனெனில் இடி, மின்னல்,

மழை கூட்டி வருவேன்”.

The entire police rampage unfolds as a mother’s cries resound everywhere, sending shivers of horror through us. Her prolonged struggle and the village’s fight rage with the pain of birth, the birth of a new life and liberation. A life is sacrificed while a new one enters the world. How gut-wrenching that the first lullaby the child hears is a lament, a funereal cry.

The climactic confrontation epitomises the core subversion of the tale. The saga of killing is one of torment and rethinks the way of justice. The killing occurs inside an old, dilapidated temple on whose walls we once again see paintings of folkloric gods, resembling Kattupechi. As Karnan does the inevitable, he does it out of regret and sorrow, breaking down in wails.

The subsequent shots after the killing are especially rousing, and to me, they come charged with the emotional center of the film. The liberated new generation which bears the stains and sins of the bloodied past are cleansed of the blood. Revelling in the new-found freedom, a foal leaps in the air, its legs unbound. The whole of the film and its struggles lead up to achieve this moment of liberation. After years of the tragedy, the ravaged land still aches with the plight of its terror and the pain of sacrifice. An uneasy peace invades the air as Karnan stands in front of Yemaraja’s painting on the wall. The grief slowly dissipates, leading to a moment of catharsis as they all finally dance their sorrow away. It is unsettling when Kaatupechi appears, applauding the merry. She vanishes into glowing fireflies, into the very spirit of the night. Remember how Pariyan ran towards the setting sun in Naan Yaar song, bearing a torch in hand. With justice, his spirit, Karnan’s and hers will rise ablaze every dawn as the raging sun.