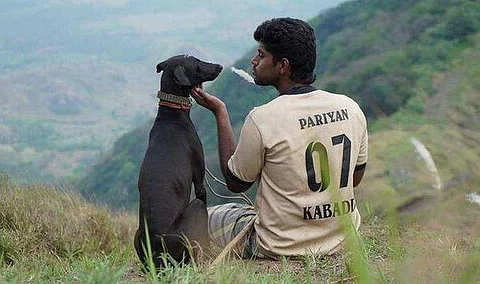

It is two years since the release of Mari Selvaraj’s Pariyerum Perumal, a seminal and sensitive political film that can be said to have yielded a new thrust to the Dalit movement in Tamil cinema. I still remember the first visuals of the film’s trailer that sent shudders through my being. A naked child steps out of the house in the monochrome visuals and whispers to us that the pet dog Karuppi has gone missing. The camera zooms into the hopeless eyes of the film’s titular character. You knew instantly that this was no ordinary filmmaker. Through almost literary sequences, the film closely explores the ruthlessness of a society steeped in communal divisions, and Mari Selvaraj, for those unaware of his past, is a powerful filmmaker who journeyed from literature to cinema.

The art that informed Pariyerum Perumal

Mari Selvaraj’s first book, a collection of twenty-one short stories, ‘Thamirabaraniyil Kollapadathavargal’ released eight years ago, on December 2012. The next year, Mari Selvaraj penned a personal memoir series for Ananda Vikatan, ‘Marakave Ninaikiraen’. This was all when he was assisting director Ram and waiting to make a film. Shook by the tears of a fifteen-year-old boy, Selvaraj wrote in Marakave Ninaikiraen that the tears were his confrontation with life as he wandered in search of stories. In all of the filmmaker’s written stories—and his film—it was life itself that I discovered in all its irony, cruelty, and poetry. As he confesses in the preface of his first book, Mari Selvaraj did not grow up listening to the tales of fabled kings, queens and witches from grandmothers but the stories his brother would narrate late into the nights, stories of everyday characters and the current of drama in them.

Raised in a rich tradition of oral storytelling, folk arts like Paavai Koothu, Sambadi aatam and an obsessive love for cinema, Mari Selvaraj’s storytelling inherits elements from all these art forms which he infuses with his depth of feeling. An emotional friend, reeling from his stories, once hailed him as a divine artist and I conceded. Ironically, in the last poem concluding his second book, Mari Selvaraj takes on divinity, renouncing responsibility and in a witty stroke breaks the truth about himself, a truth which informs his art.

In the poem which begins, ‘Siluvayil araiyapattavan enbatharkaaga, ennai kartharaga ninaithu…’, the artist claims he is no Christ simply because he was crucified. He says he could be one of those two thieves crucified alongside Christ, sinners for whom none prayed or shed tears. Who is to say which suffering is divine and which crude? Mari Selvaraj is an apostle of the unsung in a sense.

Death of a dog

His first book and debut feature share a similar opening: a gruesome killing that results in the loss of an innocent life and lament. The first story in Thamirabaraniyil Kollapadathavargal is about the murder of an aging dog. The death of such a faithful and loving being in the beginning of Mari Selvaraj’s stories plunge us into a realisation of how loveless the world is, how the line between love and hatred get breached, and how innocent lives are wrecked. In the short story titled ‘Avargal ennaku Suresh endru peyaritaargal’, the narrative is unfolded from the perspective of a dog. With caste politics raging behind the hatred, you see the pattern: they are all stories of terror and lament.

The angelic Jo

In another short, Anand-Sha that deals with love and male chauvinism, Anand tells Sha, “If one can’t enjoy the beauty of the ocean, they can’t understand the power of tears.” Beauty and brutality coexist in the literature and cinema of Mari Selvaraj. These dual forces render a poignant reality to his art, one that seethes with irony, love, wrath... A self-proclaimed admirer of Tamil poet and writer Vannathaasan’s work, Mari Selvaraj seems to have picked up on the intimate warmth in Vanathaasan’s work. Impacted by it, Mari Selvaraj can be said to focus on beauty in his works (including Pariyerum Perumal), a beauty that gets exemplified in the face of brutality. This is why Jo in Pariyerum… beams as an angelic figure, though others including her father barely perceive this. Jo, the name, is synonymous with love and hope in Mari Selvaraj’s writing in which she often appears as a friend, confidante or a means towards redemption.This is evident in his short stories Adukku Sembaruthi, Alainthu Thiriyum Perunkadal and Christmas Thaathaakal . So long as Jo exists, there lingers hope in the world.

Note also that throughout Pariyerum Perumal, Shridhar’s camera is vital and shuddering. Few frames in the film are stable, with there being a constant tension in the film that turns more prominent with the distorted angles in a song like Naan Yaar.

Pariyerum Perumal and The 400 Blows

In the preface to Thamirabaraniyil Kollapadathavargal, Mari Selvaraj shares how he changed the title of the eponymous short from ‘Thamirabaraniyil Kollapadaatha naan’ to ‘Thamirabaraniyil Kollapadathavaragal’. In a few stories, he employs the use of both the third person singular and the first person singular as he refers to himself, ‘Avan-Naan’, where he becomes his own alter-ego. This is an artist’s detachment through which he analyses life, experiences, and reconnects with and recreates life through art. This tendency of Mari Selvaraj’s art reminded me of a review I once read of Francois Truffaut’s 1959 debut, The 400 Blows, by a writer called Fereydoun Hoveyda.

In the review, Hoveyda recounts Sartre’s words, “You should know how to say we before you can say I.” Mari Selvaraj puts the ‘we’ before the ‘I’. Pariyerum Perumal is charged with intimate autobiographical elements, for films are imagined autobiographies. Mari Selvaraj writes about two films in Marakave Ninaikiraen: Prasanna Vithanage’s Death on a Full Moon Day and… of course, Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows.

Can Pariyerum Perumal be thought of as Mari Selvaraj’s The 400 Blows? It is, sure, but it is also more. Truffaut’s classic debut film deals with a delinquent adolescent and the world around him that is uncomprehending and unloving. The angst in Pariyerum Perumal, on the other hand, is more urgent as the commentary is not just about a young man coming of age but also a society.

The strong social context in Pariyerum Perumal also makes it different from The 400 Blows while the college scenes in the film are very reminiscent of Antoine Doinel’s classroom where he is constantly harassed by his teachers. Writing about Antoine Doinel, Mari Selvaraj says he sees himself as being one with Antoine. He writes, “I ran as Antoine did in The 400 Blows. He had the seas and I, the banks of Thamirabarani.” Critic-turned-filmmaker Truffaut’s film steered the historic French New Wave movement in cinema, while author-turned-filmmaker Mari Selvaraj’s debut can be thought to have driven the Dalit movement in Tamil cinema forward.

The trains in Pariyerum Perumal

The innocence of Mukilan in Mari Selvaraj’s Thamirabaraniyil Kollapadaathavargal extends to Pariyerum Perumal who has an endearing child-like habit of making promises on his mother’s name. It is in his short story that Mari Selvaraj first conceives the metaphorical apparition of the dog, Karuppi, who Mukilan encounters in the dark streets of a village after he escapes the massacre at Thamirabarani. In the ending of the short, Mari Selvaraj interweaves the ‘we’ and ‘I’, an idea he pioneers on screen with the psychedelic song, Naan Yaar, an existential cry of not just one man but a community. The origin of the song’s intense imagery lies in the poetry and imagery of Mari Selvaraj’s literature, especially in an episode in Mari Selvaraj’s second book. Walking out of the dark room in a marriage hall after a bitter confrontation, Mari Selvaraj says that all he could hear amidst the merrymaking were wails of owls pecked by blind crows under the scorching daylight.

Shrill cries of trains are portents of death in Pariyerum Perumal, like of Karuppi in the film’s prelude. Think also of Pariyan’s run in the railway tracks in the song, Naan Yaar? In his mentor Ram’s debut, Kattradhu Thamizh, too, trains were harbingers of death, as you see when Parabhakar’s dear dog Tony gets killed. It’s no surprise then that Mari Selvaraj has written a short story titled ‘Ennaku Rayilgalai Pidikaathu’. Most of his shorts are set in the vicinity of railway tracks, and hence in the proximity of uncertainty and pain. Yet, in a hopeful note, in a child-like voice, Jo asks Pariyan if they can go play with trains, exploring the possibility of becoming the innocent children they once were.

Answers through art

Mari Selvaraj raises important questions in his second book, Marakkave Ninaikiraen, in the form of verse. In a chapter called Iraiyaanmai, Mari Selvaraj writes one that seems to have powered Pariyerum Perumal:

நீங்கள் என்னிடமிருந்து

நான் என்ற எனக்கான

என் சுதந்திரத்தைப்

பறித்துக்கொண்டீர்கள்...

நான் உங்களிடமிருந்து

நீங்கள் என்ற

எனக்கான ஆறுதலையும் அழித்துவிட்டேன்...

பின் இனி எப்படிப் புழங்கும்

நமக்கிடையே நாமென்ற

அந்தப் பரிசுத்தமான சொல்?’

In Pariyerum Perumal, Mari Selvaraj’s reflections continue as he explores the many facets of his story and society. The evolution of Mari Selvaraj’s art is the story of an artist persistently and passionately furthering his exploration through different forms of art in the hopes of fathoming truth.

In Marakave Ninaikiraen, he writes of the poison that filled his teacups, a poison called caste. He invokes Alagiya Periyavan’s poems and the poison of caste that invariably filled the poet’s teacups too. You see this imagery at the end of Pariyerum Perumal, when he ends with a powerful shot involving teacups to uphold equality, a shot that is hopeful that the toxicity of caste will be vanquished through empathetic conversations. The little jasmine flower between the teacups symbolises this hope.

Mari Selvaraj will continue to reflect through art, search for answers and probe his… and our world. A world haunted by the ghosts of those killed in Thamirabarani, a world of angels, wrath, and revolution. It is a world where young kids create little mud homes by the railway tracks, so fluttering insects can rest briefly.