Two of Sylvain Chomet’s feature-length animated films—The Triplets of Belleville (Les Triplettes de Belleville, 2003) and The Illusionist (L’Illusionniste, 2010)—are often voted the best in global cinema surveys. Both recently made it to Indiewire’s list of the best animated films of the 21st century.

His third, A Magnificent Life (Marcel et Monsieur Pagnol), a biopic of the French writer, playwright and filmmaker Marcel Pagnol, is marked by the characteristic, vivid visual style, whimsicality and wistfulness of his previous films and has some stunningly realised sequences.

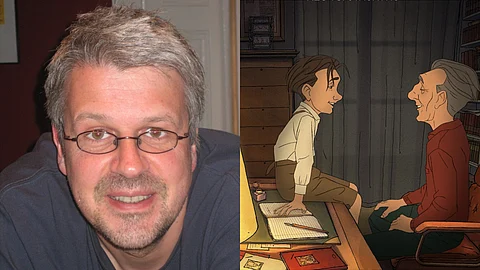

Using a unique narrative technique, of Pagnol encountering his childhood self, it captures his life in all its expanse and glory—his early years as an English teacher, his move from Marseille to Paris, his innings in theatre and becoming one of the greatest French playwrights, his fascination for cinema but the hatred for silent films, the eventual embracing of motion pictures after the arrival of sound and the setting up his own studio in Marseille.

It premiered in the Special Screenings section of the Cannes Film Festival and recently competed in the Annecy International Animation Film Festival.

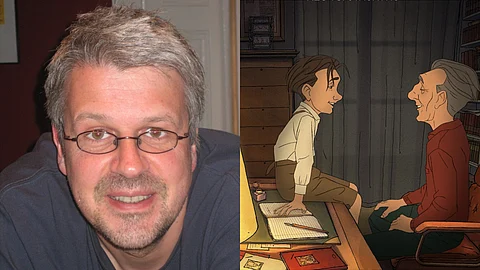

Chomet spoke to The New Indian Express/Cinema Express on why he chose to tell the story of Pagnol, what went into its making, how animation trumps over live action when it comes to biopics, about films on films and how artificial intelligence can never take over the art and craft and the artist.

Excerpts:

What made you pick an icon like Marcel Pagnol for the subject of your new film A Magnificent Life?

I wouldn’t say I was excited. At first, I was mostly scared because Pagnol is like Marcel Proust or Victor Hugo, one of the biggest names in French literature. I was approached by Nicolas Pagnol, his grandson. We became friends. It was very reassuring to have him on board, and to spend time with him. Through him, I grasped Pagnol. It’s very complicated to write something about a man when his family is still around and they are looking over your shoulder. It wasn't the case here.

Talking about doing a biopic in animation as opposed to live action, what is it about animation that challenges and what is it that can liberate a filmmaker when dealing with a biopic?

I think the main thing is to give life to people who are not there anymore. When you do biopics in live action, who is going to play them? There's always a bit of cheating there and people know that. In animation, they believe the characters are for real. So that is really cool. You can recreate everything and have people believe in it.

You have used an interesting narrative mode in the film wherein you use the vision of Pagnol’s childhood alongside the perspectives of his present self…

It was a way to illustrate, give a face to memories. I'm not talking about him as a child. That’s not the story of the film. Many films based on his books had already recounted his childhood. I wanted to show a story that people don't know. The interesting thing about Pagnol is that we all know about his childhood, and we know him at the end of his life, when he was an academician and very renowned and rich.

When it comes to the middle, there's nothing. It's a bit like Jesus Christ. We know when he was born, and then we know of him as a 33-year-old. We wonder what happened in the middle. That's basically what was interesting for me. Pagnol started quite late. He was 27 years old when he moved to Paris. He was an English teacher. He wanted to become famous, but didn't have anything. He was living in horrible hotels in Paris.

So it's very interesting to see what he went through in this period and later how he became a director, how he went from theatre to cinema, how he opened his own studio in Marseille. And then the other things in life, like his relationship with his wife. People, who love Pagnol because they found humanity in his films, are going to love this because you take that humanity back to Marcel Pagnol, the man.

The personal journey also becomes a way of charting out history and giving homage to films…

The year Pagnol was born [1895], was when the first movie got made [The Arrival of the Train or L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat by Auguste and Louis Lumière]. But he became a theatre writer, and he hated cinema because it was silent. To express emotions, a lot had to be done with the faces. He hated it until the moment in the late 20s when suddenly the sound came in and he decided to leave the theatre for cinema. He was very enthusiastic about new techniques.

Coming to the larger question of animation, how do you differentiate adult animation from that created for children and families?

I think animation is universal. It was not only for adults, but it could be for younger people and even children. I thought that I did The Triplets of Belleville (2003, Les Triplettes de Belleville) for adults. But then the kids loved it. I really hate when they say we're going to target children, because you are supposed to water down things. Everything has to be politically correct, and that's really annoying. You lose out on the power of animation. I still don't know why people are so moved by animated films. Maybe it's because when we were kids, we were drawing, and seeing the drawings actually come to life is interesting.