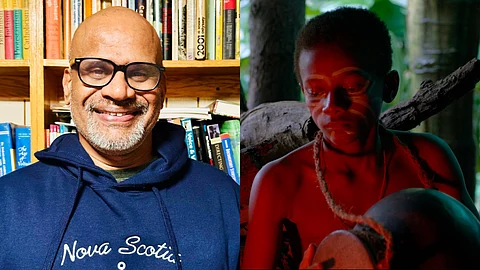

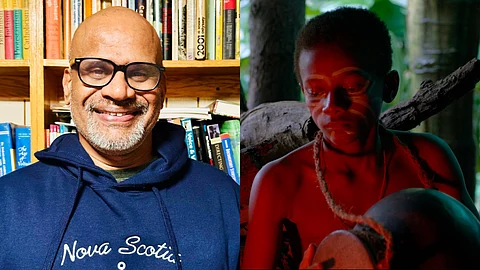

Writer-director Jayan Cherian’s Rhythm of Dammam is billed as the first-ever feature film to explore the Siddi community, the descendants of Africa’s Bantu people, and their Konkani dialect. Rhythm of Dammam, which premiered at the recently concluded IFFI festival in Goa, is set to be one of the three Indian films to feature in the International Competition section at the 29th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) later this month. Set in Yellapur, Karnataka, it revolves around Jayaram Siddi (Chinmaya Siddi), a teenager who grapples with haunting memories of his late grandfather (Parashuram Siddi). Jayaram’s family believes that the old man’s spirit continues to haunt him, but it is a metaphor for intergenerational trauma. Speaking about the origins of the film, Jayan Cherian says, "It is part of my long-time research about the subject of the African diaspora in Asia. I reached out to the community in 2016 and interacted with them for a long time. Then, I stayed permanently in their villages from 2018, which eventually led me to this film." He goes on to add, “I always had an interest in the trans-Indian Ocean slave trade. It is not as well documented as the trans-Atlantic slave trade.”

The Malayali filmmaker regards Rhythm of Dammam as an extension of his 2013 film Papilio Buddha, which talks about caste oppression, and his 2016 film Ka Bodyscapes which explores gender sexuality. It explores the struggles of a marginalised community in Karnataka. It delves into their history of enslavement and oppression, as well as their relentless pursuit of justice and dignity. Jayan feels that his prolonged inhabitation among the community and contacts with their leaders helped him make the film. “Initially, I needed my English-speaking Siddi friends to communicate with other members of the community who only spoke the local dialect. But over time, I started to pick up the language and formed a way of communicating with the community that transcended the language barriers. I immersed myself in their lifestyle over the years; hence they stopped seeing me as an outsider and embraced me as one of their own.”

A fascinating aspect of the film is its authentic exploration of the people, with their rituals and beliefs, and the way it highlights their unique language. On the one hand, is the percussion instrument Dammam, which plays a key part in the cultural celebrations and rituals of the Siddis. On the other hand, there is the Siddi language, which India is yet to recognise as an official language. Interestingly, Jayan explains that the Siddi people adapted Konkani to develop a unique dialect as a covert communication tool to converse among themselves without their masters’ understanding. As per the filmmaker, such linguistic innovation is not specific to the Siddis but rather common among similarly marginalised communities worldwide.

“I am basically a poet, so I have observed other slave groups and their specific linguistic expressions. Take the French creole in Haiti, for instance. It is interesting how the people there developed the language to make it incomprehensible for their enslavers. Likewise, the diaspora in Jamaica developed a creole language known as Jamaican Patwa,” says the filmmaker. He goes on to add, “I explored the number of dialects and words in the Bantu population, but unfortunately, they do not remember these. Add to this, the lack of serious research about the trans-Indian Ocean slave trade, which meant a lack of resources as well.”

Fascinatingly, Jayan reveals that there are differences between the languages that the Siddis speak in different areas. “The Konkani creole of the Siddis in the Karwar area differs significantly from the language of the ethnic minority in even Gujarat, let alone Pakistan. We call them all Siddis in a general sense, but they are a diverse group of people.”

Rhythm of Dammam briefly explores the relationship between a Brahmin master and his Siddi slaves. The former owns vast acres of land and exerts plenty of influence over the latter, who are of a lower socioeconomic status. In a startling revelation, Jayan says that the Siddis did not have any religion or caste of their own and that it was imposed on them. “It is the Dammam music that connects them, not religion or caste. They had to embrace the religion of their master, whether it be Christian, Hindu, or Muslim.”

Rhythm of Dammam focuses on the Hindu Siddis in the Karwar region of Karnataka. According to Jayan, there is still an oppressive system in the community in the region similar to the past. “It was shocking to me initially. The Siddis live with major landholders in North Karnataka, who own them. Some are re-enslaved from Goa, while others have been bought with cash. It is a variant of an old system in India where Dalits were bought as slaves alongside their property.”

Further adding to the above, Jayan states that the Hindu Siddis are more unlucky because they are locked in plantations. "As opposed to the Hindus, the other Siddis have more mobility because they moved out to cities in North Karnataka after gaining tribal status in 2003. All of these are just their social backgrounds as it pertains to the film. Unfortunately, those of us who have studied in India do not know about our own ethnicities or their history. It is not our fault."

From the community, there are only a handful of educated and influential, such as Kannada cinema actor Prashanth Siddi, Parashuram Siddi, Girija Siddi, and Geeta Siddi who all play important characters in Rhythm of Dammam. At the same time, however, Jayan reminds us that a generation of young and educated Siddis are taking inspiration from them.