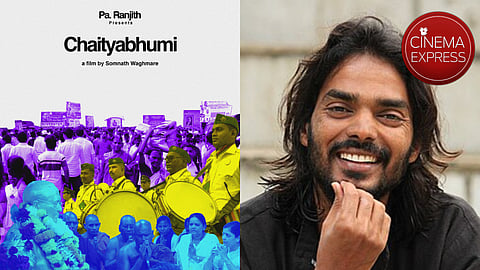

Somnath Waghmare: The government should make Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste compulsory reading in every college

In Chaityabhumi, Somnath Waghmare takes us through the emotional and cultural significance of the titular memorial in Mumbai, where Dr BR Ambedkar’s final remains are enshrined. The film showcases the site’s importance to the Dalit community and highlights how regional Dalit movements across India have evolved and interconnected over time. Somnath observes, “If you look at the map of the Dalit movement, it’s been most active in states like Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, UP, and Delhi. What’s inspiring now is that these regional movements are starting to connect with one another.” Through his documentary, Somnath provides a deep reflection on the cultural strength fostered by movements in states like Maharashtra and their vital role in shaping Ambedkar’s legacy.

In a conversation with CE, Somnath delved into his vision behind the documentary and his thoughts on how Ambedkar’s true legacy is portrayed today. Excerpts:

Could you share your earliest memory of visiting Chaityabhoomi?

Growing up in a village near Kolhapur, Chaityabhoomi and other Ambedkarite sites were part of my life from early on. In Maharashtra, Ambedkar Jayanti is celebrated with such pride—people buy new clothes, decorate their homes, and the whole community comes alive. I never had to hide my identity, which I consider a privilege rooted in the strength of the movement here. During school itself, I visited most key sites—Bhima Koregaon, Mangaon, Mahad, and Chaityabhoomi. The only place I hadn’t seen was Nagpur’s Deekshabhoomi, which I visited later during my master’s. Each of these places holds a powerful memory, and eventually, those memories found their way into my films.

The documentary has some footage from Dr Ambedkar’s 63rd death anniversary at Chaityabhoomi, and since you started filming in 2019, what prompted the five-year filming process? With so much material, how did you decide what to include in the final cut?

That’s a complicated question. My process is very research-driven. Before I start filming, I usually spend around six months doing groundwork—meeting people, recording voice notes, and understanding the geography of the place. For Chaityabhumi, I decided early on that my focus would be Dadar—I didn’t want to go beyond that.

I follow people closely, document their journeys, and only after that do I sit down, watch all the footage, and start scripting. A lot of interviews didn’t make it to the final cut because I eventually decided to shape it more like a musical film. That creative shift also guided my editing choices.

Your film focuses on Maharashtra, yet it's presented by Tamil filmmaker Pa Ranjith. In Tamil Nadu, caste discourse often revolves around Periyar and Dravidian politics rather than Ambedkar. How do you see this conversation expanding to the South?

Each state has its own discourse, like in Maharashtra, where the mass conversion movement gave the Dalit community strong cultural power, even if political power was limited. What’s inspiring now is that these regional movements are starting to connect with one another. I’ve known Ranjith since Madras. What makes him stand out is his vision and accessibility—he genuinely wants to support new voices. Unlike many in the industry, including people from the community, he actively backs fresh ideas and independent filmmakers.

I expected Ambedkar’s grandchildren to be key sources, but aside from Advocate Prakash Ambedkar’s speech and some family visuals, they weren’t featured. Was that a conscious choice?

I wanted to highlight the women in the family, especially in that Chaityabhoomi scene. But they weren’t on stage or giving speeches, which is why there’s no interview or Q&A with them. Still, I made sure to include them visually to acknowledge their presence and legacy. That’s why there’s a scene in the film where I show the entire Ambedkar family together—Sujata Ambedkar, Hrithik Ambedkar, their mothers, and even Ambedkar’s daughter-in-law, Meeratai Ambedkar. She’s quite well-known in Maharashtra and led the Buddhist Society for 15 years after her husband’s passing.

The documentary begins with Ambedkar’s house in Rajagriha in black and white and ends with a frame of Buddha before the credits roll. Was there a specific meaning behind these choices?

In our school texts, we learnt the story of Buddha and Angulimal, which centres on equality and non-violence—values that are key to the Dalit movement. For today’s generation, I felt Buddha's message of non-violence was important. The film ends with the sea, symbolising the connection between Ambedkar and the water. It ties together the themes of the sea and Ambedkar.

Your film draws parallels between Ambedkar and Chhatrapati Shivaji. Do you feel as strongly about Shivaji as you do about Ambedkar?

In Maharashtra, Ambedkar and Shivaji are two major figures followed by the masses; both are from the Konkan region, which includes Mumbai, Sindhudurg, Ratnagiri, and Goa.

Shivaji is often misrepresented in films as a communal king, but he wasn’t anti-Muslim. His son, who was a progressive Sanskrit scholar and wrote Buddha Bhushan, is rarely depicted.

In Chaityabhumi, a source mentions that Ambedkar-related spaces were built more by the people than the government. Do you think the current BJP government has done enough to honour Ambedkar as compared to other governments?

If the government truly wanted to promote Ambedkar, it should make his book Annihilation of Caste compulsory in every college, across all fields. Instead, they selectively highlight parts of Ambedkar’s work, often before he announced his conversion to Buddhism. Ambedkar's core idea was to annihilate caste, but the current government selectively uses his writings, sometimes even misinterpreting him as anti-Muslim. The truth is, they are a pro-caste government, not interested in dismantling caste structures but in maintaining dominance for a few.