One of the most widely circulated stories from my childhood revolved around astronaut Neil Armstrong allegedly converting to Islam after hearing the azaan upon landing on the moon. It was said that his conversion led to his exclusion from mainstream media and subsequent space missions. For many Muslims, it was a moment of great pride — the God we worshipped seemingly affirmed by a White man on the moon. Had people not believed this story, they might have questioned the Americans about their lunar journey: their methods, equipment, technology, and findings.

However, such questions never arose because people were already hypnotised by the tale of the azaan. As time passed, our society exhibited diminished interest in the cosmos. Instead, claims emerged of holy names being sighted on the moon. When I watched Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Heeramandi, I was reminded of this childhood rumour. His take on Heera Mandi is akin to someone who only knows the story of Armstrong hearing the azaan, making a biopic on his life.

Exhibition tour

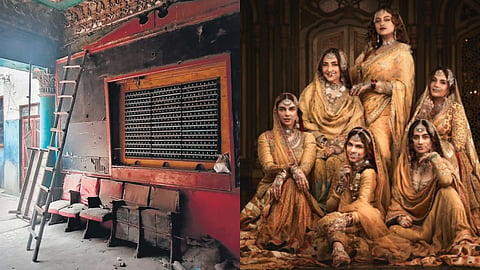

This series had the potential to shed light on the lives, culture, socio-economic status, and challenges faced by the inhabitants of Heera Mandi. It could have addressed misconceptions, societal treatment, and struggles, offering insight into their rise and fall. However, it regrettably reinforces Bollywood stereotypes, failing to foster empathy for any character. Instead, it resembles a tour of a stereotypical exhibition, showcasing grand structures and extravagant costumes at every turn.

The most unnecessary part of the series was the disclaimer stating, “any resemblance will be coincidental”. No need to worry. There is no resemblance whatsoever. The series is rife with aesthetic and historical inaccuracies, making it disconnected from any specific era or region. The architecture, language, costumes, and Nawabi culture portrayed, with its adaab and janab, have no historical ties to Lahore.

Punjab historically embraced diversity, with Sikhs, Muslims, and Hindus coexisting in various spheres of life. However, Heeramandi consistently depicts tawaifs as Muslim women, speaking in Lucknavi Urdu, regardless of their actual backgrounds. Lower-income individuals are also shown speaking Punjabi and laughing at their own jokes.

This perpetuates the colonial mindset — colonial Britishers would degrade the language and show that it is only spoken by servants; Punjabi culture and their heroes were especially debased for Muslim Punjabis so that they move towards English and Urdu — that Bollywood elites should have outgrown long ago.

Lusty, greedy stereotypes

In historical context, there were designated spaces for artists, both residential and performance-based. Those interested in music, poetry, and the arts would visit these spaces to engage with relevant individuals, much like modern-day art spaces and theatres. Figures such as Ustaad Daman and Allama Iqbal resided in such areas. However, instead of portraying the intellectual richness of these communities, the series reduces them to lustful and greedy stereotypes.

This phenomenon is, however, not new or restricted to India. In 2000, Parliament Se Bazaar-e-Husn written by Zaheer Ahmed Babar, a Pakistani, was a sensation during Musharraf’s martial law era, offering alleged sex stories of Pakistan’s ruling elite. Instead of engaging with democratic and economic failures, people believed that if the elites abandoned their secret desires, the country would prosper. This oversimplification of history attributes the East India Company’s rule solely to the sexual frustrations of the elite, disregarding broader historical dynamics. Heeramandi’s portrayal is another example of this trend. It seems that Bhansali’s portrayal of Heera Mandi focuses solely on one emotion: seduction.

Heera Mandi’s other images

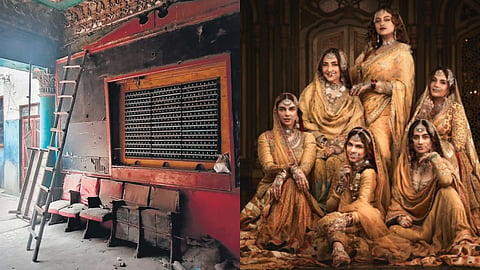

Heera Mandi’s ruins are a testament to Lahore’s history and the broader cultural fabric of Pakistan. The Mandi, has long been celebrated for its delectable cuisine, epitomised by Phajja’s iconic shop adorned with photographs of celebrities and politicians who savoured Lahore’s traditional breakfast here. However, alongside this culinary tradition, a modern food street has emerged, drawing visitors with its proximity to the Lahore Fort and the Shahi Mosque. Tourists these days flock to Heera Mandi for traditional Khussa footwear; aficionados seek musical instruments. The area also beckons art students, who wander its streets, capturing its architectural splendour. It serves as a sought-after location for fashion shoots and film productions.

Nevertheless, despite its undeniable charm and historical significance, Heera Mandi lags behind the rest of Lahore in terms of development. Its streets remain narrow, cluttered with refuse and choked by traffic. Yet, amid the dust and chaos, glimpses of exquisite architecture and intricate woodwork adorn the aging homes.

During our teenage years, stories about Heera Mandi were full of curiosity, depicting women hanging out of windows, jeering at passersby, and pimps whispering prices on the streets. That was the prominent image I had of the Mandi. However, a few years later when I was a university student, I had the opportunity to view Iqbal Hussain’s paintings at an exhibition. Hussain, who hailed from Heera Mandi, captured the everyday life of the area with rough strokes, an unconventional colour palette, and expressive portrayals of out-of-shape bodies. His work was imbued with social commentary, and as I observed, the childish stories I had heard faded away. Although I did not personally know the women depicted, I felt a profound connection to their stories.

Two images, in particular, remain vivid in my mind: one depicting a young girl lying on a bed with arms outstretched, holding coins in her hands, and the other showing the death of a woman, with children standing beside her, saluting. These images offered a glimpse into the reality of life in Heera Mandi, unlike the sensationalised perspectives often portrayed. I wish the writers and directors had delved into authentic literature and art to present the story from the tawaif’s perspective, rather than a “tamash been”. While I do agree Bhansali is an undisputed God for wedding photographers, fashion designers and event planners, it is important to recognise that true understanding of relationships and communities cannot be gleaned solely from surface-level portrayals. We cannot understand the depth of a relationship between a wife and husband by merely looking at wedding albums.

Adeel Afzal is co-writer of the recently aired Pakistani TV serial, ‘Standup Girl’, and an actor. He has acted in the drama serial, ‘Parizad’, and a film, ‘Zindagi Tamasha’.