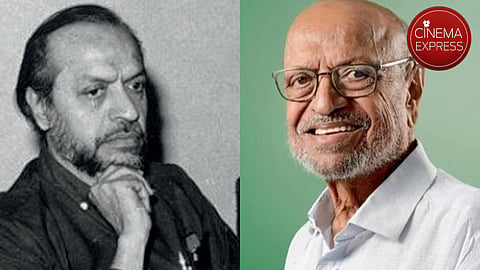

Shyam Benegal: Framing India in a Catholic aesthetic

Nationalist would be the most erroneous description to use for Shyam Benegal, even though his cinema remained perennially committed to the vital idea of India. Far from the jingoistic, exclusionist, chest-thumping associations of the word, Benegal’s was a Catholic and humanist vision of the nation. It was driven by the intention to introspect on the inherent contradictions of our polity, economy, and the social landscape rather than be a flag bearer of belligerence and supremacy. Benegal’s was the cinema of inquiry rather than exaltation. It addressed the significant phases in the life of the nation but was also timeless in its appeal, resonance, and relevance. Cinema that was intuitive, insightful, and also far-sighted.

No wonder the defiant stone that the underprivileged, anonymous boy threw at the arrogant and exploitative landlord’s window in the iconic climax of his first feature, Ankur (1974), ricocheted with as much pent-up rage and resistance four decades later when Jabya hurled the rock at the camera, and in turn the audience, in the equally memorable last scene of Nagraj Manjule’s debut feature, Fandry (2013), making us rightly complicit in the unending scourge of disparities, discrimination, violence, and violation.

Benegal continued to explore the broad themes of exploitation of the vulnerable—be it related to divides of caste, class, religion, or gender—in films dealing with India’s contemporary reality, with women in special focus, like Nishant, Manthan, Mandi, Susman, Samar, Hari Bhari, Welcome to Sajjanpur, and Well Done Abba. The underlying message was always that of emancipation and empowerment and the way out through collective resistance, people’s movements, and cooperatives.

Mahatma Gandhi, Subhash Chandra Bose, and Mujibur Rahman became subjects of his subcontinental biographical films. There were fictional/literary Indian histories he turned to in Junoon (British rule) and Trikal (the Portuguese colonisation of Goa), where the dangerous liaisons inside the domestic/familial space ran parallel to the political turmoil of the freedom struggle outside. And an Indian mythological text like The Mahabharata got reinvented in the light of the contemporary economics and corporate culture in Kalyug. But the most vivid documentation of India happened in four of his TV series—Yatra (a journey on India Railways’ Himsagar Express), Bharat Ek Khoj (based on Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery of India), Sankranti (on various legislations of Indian government in 50 years since Independence), and Samvidhaan (on the making of the Indian Constitution).

In a nutshell, an entire enviable body of work that pivoted on India was all about the past, present, and future of a nation in the making and on the move.

One dramatis personae often present in these explorations was Mahatma Gandhi. The Making of the Mahatma in 1996 had Rajit Kapur essaying Gandhi’s South Africa years, Neeraj Kabi portrayed him in Samvidhaan (2014), and Gandhi was an inevitable presence in Bharat Ek Khoj and Sankranti as well. To mark Gandhi’s 150th year, I remember talking to Benegal for The Hindu about what made him special for a filmmaker like him. He called Gandhi “the only person in Indian history you can portray subjectively without raising hackles.” “Gandhi can never become irrelevant because his ideas are simple, straightforward, compassionate, and humane, making them universally applicable,” he added.

Like Satyajit Ray, Benegal transitioned from a successful career in advertising to filmmaking. Like Ray, he also brought an acute sense of realism to his films. However, like his cousin Guru Dutt, he also understood the drama, emotions, and musicality of popular Indian cinema. The understanding and amalgamation of the two in his films resulted in cinema that was artistic and sophisticated, but not esoteric, that involved the viewers rather than alienating them.

I remember being surprised by the inclusion of the title song of Kal Ho Naa Ho in his list of favourites for an industry poll for Outlook magazine on the all-time best songs of Hindi cinema. How could a filmmaker with Vanraj Bhatia as his musical muse and the one who had songs in his films like Baju re Mondar' sung by Hindustani classical music vocalists, Saraswati Rane and her granddaughter Meena Fatherpekar, or Mohammad Rafi’s 'Ishq ne todi sar pe qayamat' and Asha Bhonsle’s 'Ghir aayi kari ghata matwali' opt for a Shankar-Ehsaan-Loy ditty? I asked him gently, and he answered with a counter-question: why not? For him it had both melody and meaning, which he considered essential for music-making.

Unlike a lot of arthouse filmmakers, Benegal was never condescending of mainstream cinema even when critiquing it. In one of my earliest interviews with him for India Today, he spoke about the possibility of casting someone like Govinda in his films. “The problem is with the strong public image of our stars. The viewers find it difficult to separate the screen character from the star. But I'm willing to experiment. That's filmmaking for me,” he said. And later he did go on to walk the talk and work with the likes of Karisma Kapoor, Amrita Rao, and Manoj Bajpayee.

On the very day the legendary filmmaker passed away, I had transcribed an interview with the British-American actor Andrew Garfield, where he spoke about how a film set is a relatively lonely space as compared to the community feel of theatre. Benegal’s cinema was as much about him as about his bunch of steadfast collaborators. A set that kept growing as he kept introducing and nurturing new talent. Vijay Tendulkar, Satyadev Dubey, and Shama Zaidi for writing; Govind Nihalani, Ashok Mehta, and Rajan Kothari to wield the camera; Vanraj Bhatia and Preeti Sagar for music; and an entire ensemble of virtuoso actors, many of them from FTII and NSD—Girish Karnad, Amrish Puri, Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, Om Puri, Naseeruddin Shah, Anant Nag, Sadhu Meher, Neena Gupta, Ila Arun, KK Raina, Rajit Kapur, Surekha Sikri—and later Shashi Kapoor joining hands as both producer and actor.

Girish Karnad used to talk about how Benegal had been a friend, philosopher, and shrink to the people he worked with. “But these are roles most directors get caught with. Unlike a painter who works with paints and brushes, which cannot complain, we are dealing with human beings,” said Benegal. He spoke of it as an inevitable privilege of working with intelligent people. “Filmmaking is a wonderful picnic, a great adventure, where you're constantly discovering new things,” he told me.

For him, cinema was amongst the biggest and most extraordinary inventions of the late 19th century, especially in India, where films are made in more languages than any other country in the world. “It managed to cast a spell across the world. It’s a work of art and the biggest source of entertainment. Cinema has taken over our imagination in a way very few things have,” he said in an Outlook special issue to mark the centenary of cinema.

Fittingly then, one of the last big moments for Benegal was the screening of the restored version of his Manthan (done by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s Film Heritage Foundation) in the Classics segment at the Cannes Film Festival in May this year. A celebration led by one of his favourite actors, Naseeruddin Shah, in his own absence due to ill health. What made it even more special was the fact that sharing space with a towering figure like him in Cannes was the newer bunch: FTII graduate Payal Kapadia with her All We Imagine As Light in the main competition, FTII student Chidananda Naik’s Kannada short Sunflowers Were the First Ones to Know in the LaCinef student section, and Kapadia’s batchmate at FTII, Maisam Ali’s In Retreat, showing in the ACID sidebar. A wonderful coming together of a maestro and the emerging talent. Incidentally, Benegal himself served as FTII chairman twice: 1980–83 and 1989–92.

Another significant role he played was to head the Benegal Committee of 2016 on the revamp and reform of the CBFC. The Benegal Committee and the Justice Mukul Mudgal Committee of 2013 had both suggested, among other things, moving away from censorship towards age-based rating/classification norms for films. Perhaps a great way to honour one of Indian cinema’s leading lights would be to implement some of the progressive suggestions for the good of Indian cinema at large.

My Benegal Picks

1) Bhumika (1977)

Based on Sangtye Aika the memoirs of the well-known Marathi stage and screen actress of the 40s, Hansa Wadkar, it is one of the most layered and complex portrayals of a flawed woman searching for freedom and self-determination even while succumbing to exploitation. Smita Patil at her best and great songs like 'Saawan ke din aaye sajanwa aan milo' and Tumhare bina jee na lage ghar mein.”.

2) Kalyug (1981)

The film on intrigue and feuds in a business family draws from The Mahabharata and makes for Benegal’s most riveting. Tightly scripted and nimbly paced with Shashi Kapoor in great form as a Karna-like figure.

3) Bharat Ek Khoj (1988)

Based on Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery of India, Benegal’s series is a sprawling and ambitious exploration of the various historical eras and landmarks, the kings and kingdoms, the poets and epics, the Renaissance and Revolt, the freedom movement, and the Partition. India in 53 episodes.

4) Suraj Ka Saatvan Ghoda (1992)

Based on Dr. Dharamvir Bharati’s novella, it’s Benegal’s most intricate and abstract yet highly compelling work. Made up of various stories, threads, or strands, incorporating multiple points of view, at one level the film is about the art of storytelling and, at another, about the complicated man-woman relations and the many struggles underlying them.

5) Mammo (1994)

When a visa comes in the way of relationships. Mammo is a lovely, immensely moving film on the predicaments of a woman who has been thrown out of her house by her relatives in her home country and who can’t find a home at her sister’s place in the neighbouring country that she had moved out of at the time of the Partition. Farida Jalal at her most luminous.

6) Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008)

A charming slice of North Indian mofussil life, caught between conservatism and modernity. Caste, crime, and politics; marginalisation of Muslims and Islamophobia; illiteracy and superstition—the film ticks many issues but with humour intact.